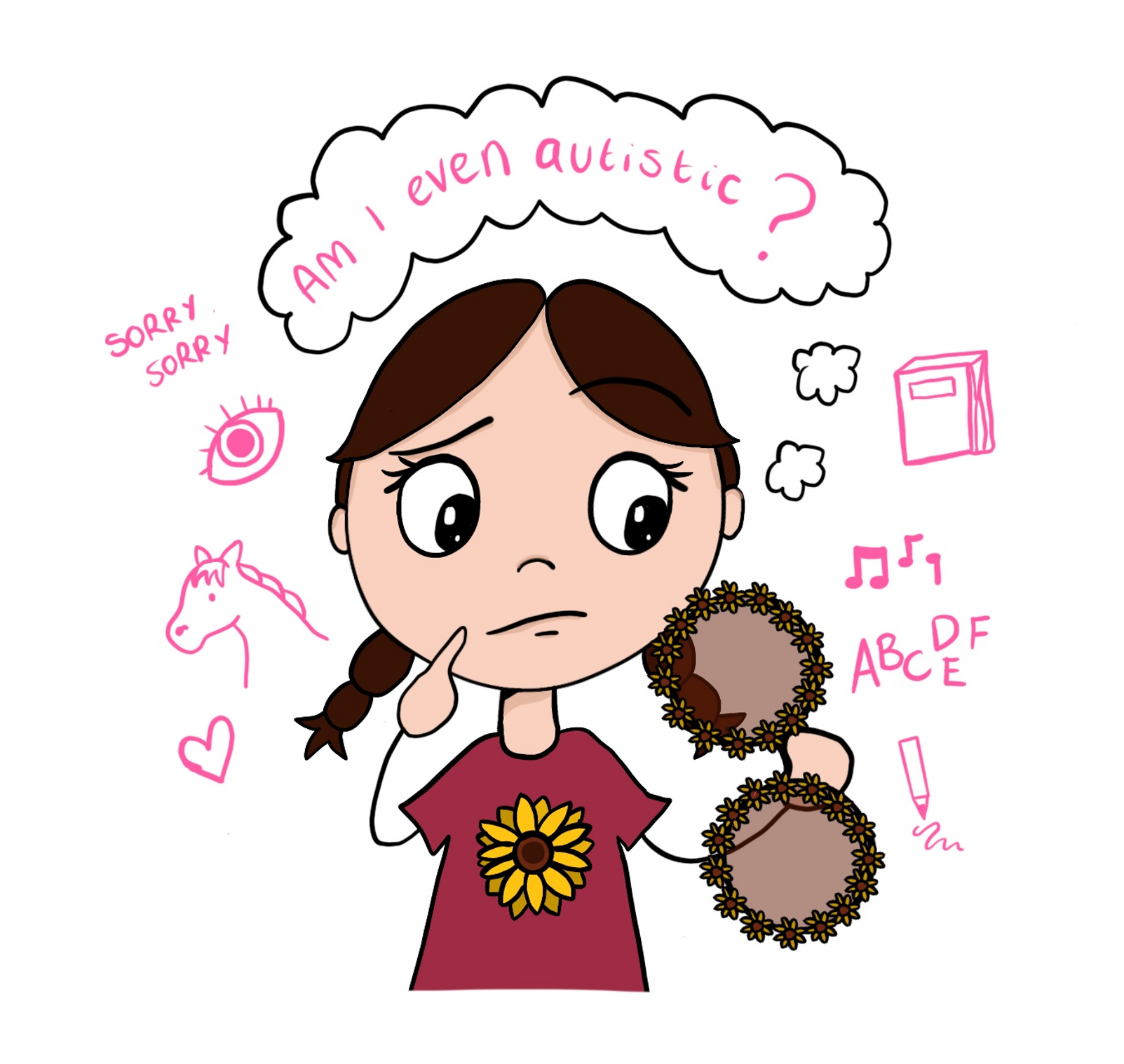

Something I’m really passionate about raising awareness of, that I don’t hear about often, is the different ‘phenotypes’ or presentations of autism, which are usually defined as ‘female’ and ‘male’. The gender differences in autism spectrum disorder are part of the reason why so many girls go undiagnosed or are not diagnosed until much later in life – in fact, it is only recently that much research at all has focused on the ‘female presentation’. For many years, the ‘classic’ or original presentation of autistic traits was the only one to be recognised! (Please note that in this post I use the terms ‘female’ and ‘male’ to refer to AFAB (assigned female at birth) and AFAB (assigned male at birth) in order to reference literature using the former terms).

When we think of autism, we think of what is now considered to be the ‘male presentation’. Some examples of symptoms we might include here would be lack of interest in social interactions, avoiding eye contact, saying inappropriate things at times, speaking over people, being unable to use or read body language and facial expressions, having very intense interests about certain topics, possibly exhibiting aggressive behaviour, and the display of repetitive movements such as head banging, hand flapping, or spinning.

However there are key differences between this classic presentation, and how many autistic females or AFABs present. While the exact reason behind this isn’t clear, some of the possible causes are:

- Genetics – some studies suggest the female/AFAB sex is ‘protective’ towards ASD susceptibility, for various reasons. For example, females experience more mutations of genes, and because males seem to have a higher expresson of genes implicated in ASD, such as chromatin regulators and those related to immune involvement. A study has also suggested that mutations in a gene called NLGN4 are linked to autism, and that NLGN4 is only present on X chromosomes (AMABs/males have an X and Y sex chromosome, while AFABs/females have two X chromosomes) – it is important to remember that these studies are very speculative, however!

- Environmental/social factors – many environmental factors have been noted to influence how autism presents. Parents seem to expect more socially desired behaviour from AFABs/girls than AMABs/boys, and interactions with neurotypical peers differs. More autistic AFABs/females are reported to ‘camouflage’ or ‘mask’, i.e. to act in a way to compensate or hide their differences, and to ‘learn’ strategies to help them manage ‘mismatched demands from the social environment’ (Mandy, 2019). This is achieved through careful evaluation of the ‘nuances of people’s actions, emotional atmosphere, and social conventions (Simcoe, 2022).

Regardless of the reasons driving the differences, we do know there are two clear phenotypes. The main differences between these are:

- Social interactions. This includes: greater desire to interact with others, masking or displaying compensatory strategies, better imagination (and may fantasize and escape into fiction and pretend play), displaying eye contact and using gestures, and developing intense friendships. They may also display people-pleasing behaviour, and apologise frequently.

- Interests and obsessions. This includes: restricted interests tending to involve people or animals rather than objects or things, e.g. horses, soap operas, pop music, fashion, literature, tendency to be extremely thorough, tendency to be perfectionistic and determined, tendency to be controlling in play with peers, exhibiting ritualistic behaviours such as making excessive lists or following certain routines, and changing fixations more often.

- Linguistic and communication abilities. This includes possessing an advanced vocabulary, and being more aware of, and mimicking, mannerisms and literal language.

- Other. Females also have been observed to display higher avoidance of stress and pressure, greater exhaustion (usually attributed to masking), more difficulties with executive function tasks, higher rates of anxiety and depression and other mental health issues (also attributed to masking and societal pressure), and to be less likely to be hyperactive and impulsive.

I would like to add that while there are significant differences between presentations, there are also lots of similarities – for example, both males and females experience sensory difficulties. And, ultimately, both phenotypes feature the same four areas of difference in some form.

Another important point to stress is that autism is a spectrum ‘disorder’, and therefore there is often overlap between these two presentations, and an autistic AMAB/male might present in a ‘female way’, or vice versa. I like to think of it as people presenting in a ‘more male’ or ‘more female’ way, rather than strictly defining the presentations as a certain gender!

Even if the distinctions between the two presentations, and their causes, are unclear, I do think it’s incredibly important to acknowledge them. When I was first diagnosed, very little was known about the female presentation, and as a result, I really didn’t identify as autistic until I was an adult. Now I know much more about how the autistic traits relate to me and my personality, I have been able to understand who I am, and this has helped me grow so much in confidence. I’ve also been able to accept the things I struggle with, and to actively develop techniques to help me live life.

Finally, at least most of the time, I feel proud to be me.

Works Used:

Halladay, Alycia K, et al. “Sex and Gender Differences in Autism Spectrum Disorder: Summarizing Evidence Gaps and Identifying Emerging Areas of Priority.” Molecular Autism, vol. 6, no. 1, 13 June 2015, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4465158/, 10.1186/s13229-015-0019-y.

Hull, Laura, et al. “Gender Differences in Self-Reported Camouflaging in Autistic and Non-Autistic Adults.” Autism, vol. 24, no. 2, 18 July 2019, p. 136236131986480, 10.1177/1362361319864804.

Lai, Meng-Chuan, et al. “Sex/Gender Differences and Autism: Setting the Scene for Future Research.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 54, no. 1, Jan. 2015, pp. 11–24, 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.003.

Lundin, Karl, et al. “Functional Gender Differences in Autism: An International, Multidisciplinary Expert Survey Using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Model.” Autism, vol. 25, no. 4, 2 Dec. 2020, pp. 1020–1035, 10.1177/1362361320975311.

Simcoe, Sarah Mae, et al. “Are There Gender-Based Variations in the Presentation of Autism amongst Female and Male Children?” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 13 July 2022, 10.1007/s10803-022-05552-9. Accessed 8 Sept. 2022.

Leave a Reply